These paradigm-shifting Phase 2 clinical trial results were published online June 16, 2023, in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

“Our findings suggest that the mechanisms driving this disease are in large part independent of excessive eosinophil production. That means our attention should turn towards other therapeutic targets to find curative treatments and that how we define remission for this disease should be reconsidered,” says Marc Rothenberg, MD, PhD, corresponding author for the study and one of the world’s foremost authorities on eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGID).

Rothenberg directs the Division of Allergy and Immunology at Cincinnati Children’s. He also leads the Cincinnati Center for Eosinophilic Disorders (CCED) at Cincinnati Children’s and serves as principal investigator and co-leader of the national Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers (CEGIR).

Rothenberg has devoted decades to studying and treating children living with this collection of severe inflammatory reactions to otherwise common foods. For many, the allergic reactions are so strong that they must follow extremely strict and limited diets. The eating difficulties can limit growth and lead to other longer-term complications.

What are EGIDs?

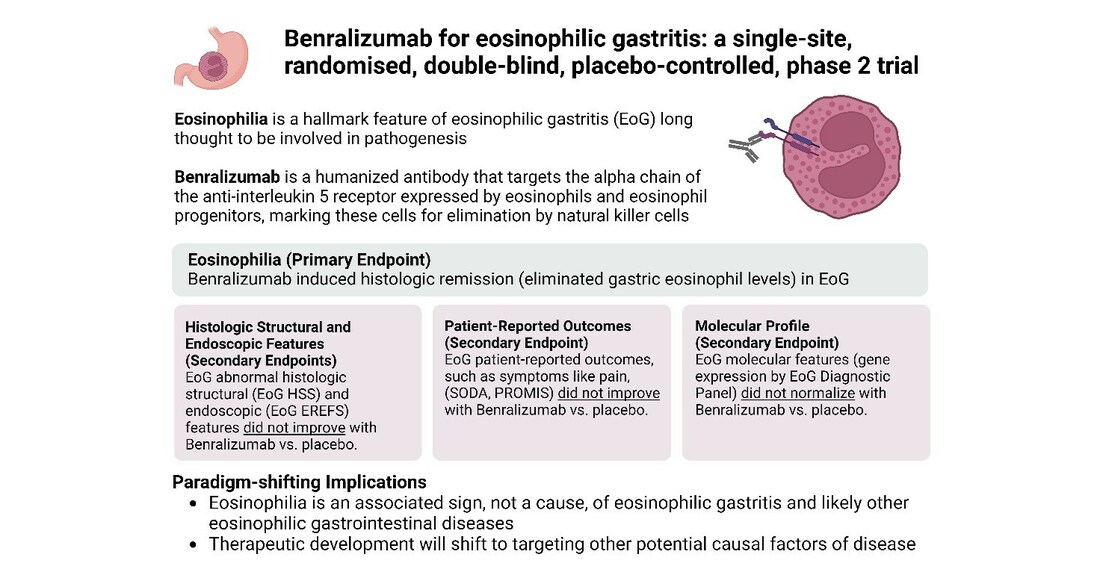

EGIDs have been distinguished from other food allergies because symptoms typically do not occur immediately after consuming the offending food. Patients with EGID have abnormally high levels of eosinophils in their digestive tract tissues. Eosinophils are one of several types of white blood cells that are part of our normally protective immune system. But they occur in high amounts in certain diseases such as EGID and asthma. In the case of asthma, eosinophils can promote excessive inflammation and tissue damage and reducing their levels can have substantial clinical benefit. But the exact role of eosinophils in EGID has not yet been determined.

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is the most common EGID, affecting an estimated 1 in 2,000 people (or about 166,000 people in the US). Less than 50,000 people in the US, combined, are believed to have other EGIDs including eosinophilic gastritis, eosinophilic enteritis, and eosinophilic colitis.

Over the years, eosinophil counts have emerged as the key biomarker for tracking the severity of EGID. Pharmaceutical companies also have been testing new and existing biologics and other treatments for their ability to reduce eosinophil counts. Benralizumab, made by AstraZeneca, is one such drug, as it safely removes eosinophils from the body and is now approved therapy for severe asthma associated with eosinophils.

Mixed results for eosinophil-depleting drug.

The study conducted by Kara Kliewer, PhD, Rothenberg, and their colleagues involved 26 patients with active eosinophilic gastritis disease, ages 12 to 60, who were randomly assigned to receive either the treatment drug or a placebo. Participants received three injections each across 12 weeks.

Of the 13 who received the drug, 10 achieved technical “remission.” That means the number of eosinophils in their blood and stomach dropped substantially, in fact, almost to zero.

However, there were no statistically significant differences in symptoms including pain, endoscopic findings, quality of life scores, or other measures reported between the drug and placebo groups. Although structural tissue abnormalities improved for six of the 13 drug-treated participants, they worsened or remained the same for the other seven. Meanwhile, an analysis of 48 genes known to be affected by eosinophilic disorders showed no improvement in abnormal expression patterns.

“These findings provide compelling evidence for a changed paradigm, shifting attention away from eosinophils as the main contributor and biomarker in eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases,” says Kliewer. “Thus, successful management of eosinophilic gastritis may require inhibiting pathways that more broadly reduce type 2 inflammation rather than only targeting eosinophils.”

What does this mean for patients and families?

Mostly, these results suggest that patients will have to wait longer for improved treatments to be developed for eosinophilic gastritis, Rothenberg says. However, our Cincinnati Children’s research team’s multiprong research approach means that several other treatment avenues were already being pursued in parallel to eosinophil-depleting possibilities.

Current standard treatments, such as diet management, anti-inflammatory steroid medications and pain relievers, should continue. If patients are receiving off-label treatments with IL-5 blockers (eosinophil-depleting drugs), they are not likely to see significant benefits, Rothenberg says.

Families with specific questions are encouraged to contact the specialist managing their child’s care.

Next steps

Researchers are likely to shift their focus to intensify studying therapies that act against other aspects of eosinophilic disease.

In 2022, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of dupilumab—a drug already approved for treating eczema and asthma–as the first treatment specifically approved in the US for EoE. This drug, also a monoclonal antibody, blocks interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling, thus targeting type 2 inflammation rather than just eosinophils.

Rothenberg was a co-first author of the study that laid out the Phase 3 clinical trial results, which were published in The New England Journal of Medicine. The symptom improvement seen in dupilumab- treated patients with EoE suggests that it may also work for the other less common forms of EGID. Through CEGIR, Rothenberg and other national experts are currently testing the theory that dupilumab may be beneficial for other forms of EGID, such as eosinophilic gastritis.

Meanwhile, Rothenberg says CEGIR is using the current findings to revise practice guidelines for EGID treatment so that they rely less heavily on eosinophil counts as a biomarker.

“Many people had high hopes that depleting eosinophils would make a large impact on EGIDs, but this is why clinical trials are so important,” Rothenberg says. “Even when results are disappointing, we learn from them and that allows us to move on to other potential approaches to improve outcomes.”

About this study

In addition to Rothenberg, Cincinnati Children’s co-authors for this study included first author Kara Kliewer, PhD, Cristin Murray-Petzold, BS, Margaret Collins, MD, Juan Abonia, MD, Scott Bolton, MD, Lauren DiTommaso, BS, Lisa Martin, MD, Xue Zhang, MD, Vincent Mukkada, MD, Philip Putnam, MD, Erinn Kellner, MD, Ashley Devonshire, MD, Justin Schwartz, MD, Chen Rosenberg, MD, John Lyles, MD, and Tetsuo Shoda, MD.

Co-authors also included Vidhya Kunnathur, MD, from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, and Amy Klion, MD, with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID).

This study was funded primarily by AstraZeneca.

SOURCE Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center